Orhan Pamuk’s My Name is Red, first published in Turkish in 1998 and later translated into English by Erdağ Göknar, is a sprawling historical novel set in late 16th-century Istanbul during the reign of Sultan Murad III. The book is part murder mystery, part philosophical meditation, and part love story, framed within the world of miniature painters in the Ottoman Empire. With its layered narration, complex themes, and interplay between East and West, the novel has often been described as Pamuk’s masterpiece.

The story opens with an unusual voice — that of a corpse. The murdered victim, one of the Sultan’s miniaturists known as Elegant Effendi, narrates from beyond the grave, setting the tone for a novel where chapters are told by a kaleidoscope of narrators: painters, lovers, a dog, a coin, even the color red itself. This shifting perspective builds a mosaic of the story while immersing the reader in the intellectual, religious, and cultural debates of the time.

At the center of the plot is a commission given by the Sultan. He secretly orders his court painters to produce a book celebrating his reign in the Venetian style of portraiture, which was seen as controversial in the Islamic world. While traditional Islamic art valued anonymity and stylized depictions, Western art emphasized individuality, perspective, and realistic detail. This clash of aesthetics frames the broader tension between East and West, tradition and modernity, faith and skepticism.

When Elegant Effendi is murdered, suspicion falls on the circle of miniaturists. Three prominent artists are central to the investigation: Olive, Stork, and Butterfly — nicknamed for their painting styles. They each deny involvement, but each has motives connected to pride, rivalry, or fear of change.

Parallel to the murder plot is a love story. Black Effendi, a former apprentice to the head miniaturist Master Osman, returns to Istanbul after years of absence. He is still in love with Shekure, the beautiful daughter of Enishte Effendi, who is supervising the Sultan’s secret project. Shekure, however, is trapped in a complex domestic situation: her husband has disappeared in battle, her father is aging, and her children need protection. Black’s return rekindles their romance, but he must also navigate the suspicions surrounding the murder.

As the investigation unfolds, questions about art and identity deepen. Who killed Elegant Effendi? Is the crime tied to the forbidden European styles infiltrating Ottoman art? Could it be that painting too much like a Venetian threatens not only tradition but also the souls of the artists themselves?

The climax comes when Enishte Effendi, Shekure’s father and the overseer of the Sultan’s project, is also murdered. The narrative tension sharpens, and Master Osman, the aging chief miniaturist, takes Black to the palace library in search of answers. There, surrounded by centuries of artistic tradition, Master Osman blinds himself with a needle — a symbolic act of both devotion to tradition and despair at the inevitable loss of the old ways.

In the end, the murderer is revealed, but Pamuk complicates the resolution: the confession is as much about artistic philosophy as it is about guilt. Black marries Shekure, but their union is tinged with ambiguity and compromise. The novel closes not with a neat solution, but with reflections on the meaning of art, memory, and the stories we tell to preserve our place in history.

Themes

- East vs. West.

At its heart, My Name is Red dramatizes the confrontation between Islamic art and Western Renaissance traditions. The Sultan’s commission symbolizes this collision: should Ottoman artists imitate European styles, or should they remain faithful to the timeless, anonymous traditions of Islamic miniature painting? This tension echoes broader political and cultural questions about modernization, identity, and power. - The nature of art.

The novel is as much a meditation on art as it is a narrative. Pamuk explores whether an artist’s individuality should shine through their work or whether art should be devoted to timeless ideals. The miniaturists’ debates about blindness, memory, and divine inspiration evoke questions about the purpose of creativity. - Love and desire.

The romance between Black and Shekure humanizes the novel’s grand philosophical debates. Shekure is not merely an object of desire but a shrewd, pragmatic woman trying to secure her children’s future. Her choices reflect the limited agency available to women, but also the resilience with which they navigated social constraints. - Murder and mystery.

While the book contains the mechanics of a whodunit — multiple suspects, hidden motives, eventual confession — the mystery is ultimately a vehicle for deeper inquiries. The identity of the murderer is less important than the way the crime illuminates the conflicts between tradition and innovation. - Multiplicity of voices.

Pamuk’s narrative technique is striking. Every chapter is told from a different point of view, including inanimate objects and abstract concepts. This polyphonic structure mirrors the art of miniature painting itself — small details creating a grand design. It also reflects Pamuk’s central question: whose story is history, and who gets to narrate it?

Pamuk’s style blends lush historical detail with philosophical digressions. The language, even in translation, is richly metaphorical, weaving together sensual description and intellectual debate. The shifting narrators demand patience from the reader, but they reward attention with depth and complexity.

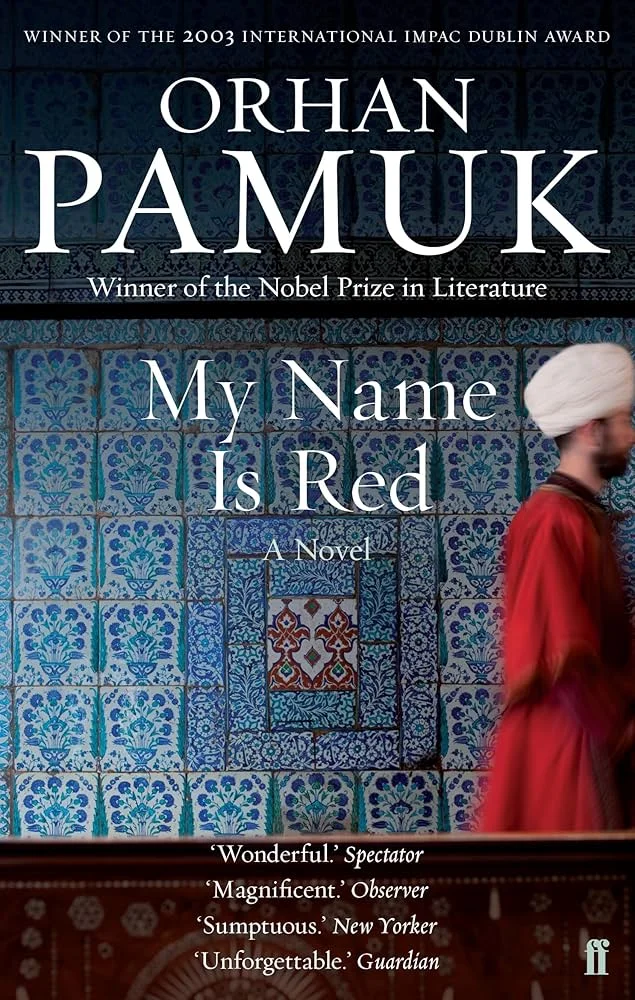

Upon its release, My Name is Red was praised internationally for its ambition and originality. It won the International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award in 2003 and is often cited as one of the works that contributed to Pamuk’s Nobel Prize in Literature in 2006. Critics admired its fusion of a detective story with metafictional reflections on art and storytelling. Some readers, however, found the pace uneven and the philosophical passages dense, making it a challenging read.

My Name is Red is not a conventional historical novel or mystery; it is a layered meditation disguised as a story of crime and love. Pamuk succeeds in creating a narrative that is at once entertaining and intellectually rigorous. The murder mystery keeps readers engaged, while the broader questions elevate the novel into the realm of philosophy and aesthetics.

The greatest strength of the book lies in its structure. By allowing even objects and colors to speak, Pamuk reminds us that history is never told by a single voice. Just as miniature paintings combine countless tiny brushstrokes into a grand image, so too does the novel assemble disparate perspectives into a portrait of an era.

At the same time, the novel demands much from the reader. Its slow pace, digressive style, and density of historical detail may frustrate those expecting a straightforward thriller. But for readers willing to surrender to its rhythm, the book offers a rich, unforgettable experience.

Pamuk’s treatment of East-West encounters is also remarkably nuanced. Rather than reducing the conflict to a binary clash, he shows the entanglement of traditions and the difficulty of preserving cultural purity in a world of exchange. In this sense, My Name is Red speaks not only to 16th-century Istanbul but also to contemporary debates about globalization, identity, and the value of tradition in modern life.

My Name is Red is a novel that resists simple categorization. It is at once a love story, a murder mystery, a historical reconstruction, and a meditation on art and philosophy. Its polyphonic voices create a narrative tapestry as intricate as the miniature paintings it describes. While its density may daunt some readers, the novel rewards persistence with a profound exploration of how art, history, and desire intertwine.

For anyone interested in literature that bridges East and West, delves into the philosophy of art, and challenges the conventions of narrative, Pamuk’s My Name is Red remains a towering achievement. It is a book that lingers, not only for the mystery of its plot but for the richness of its ideas — a work that invites rereading, much like returning to study the details of a miniature painting.